|

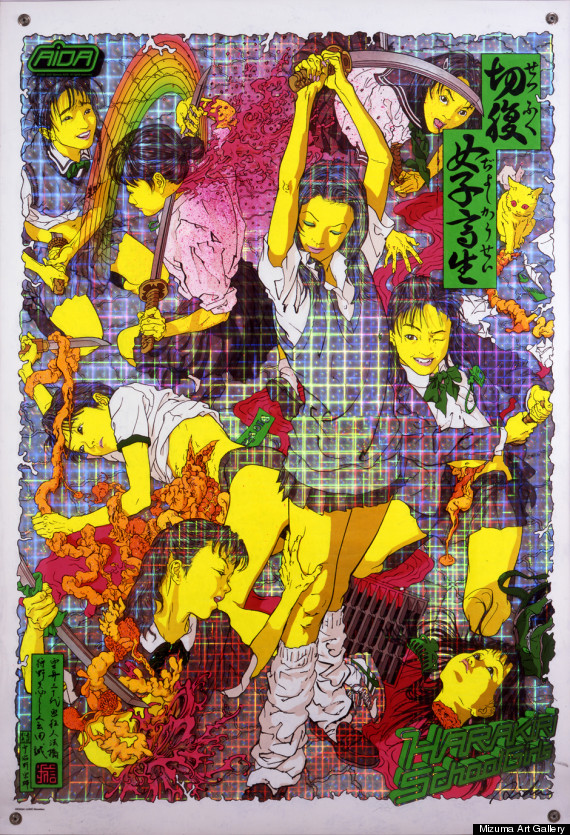

| Makoto Aida |

|

| Dog series |

Various media outlets have reported the news differently including mainstream news papers and foreign press. Japanese mainstream media such as Daily Yomiuri Online (reported in English), Mainichi.jp (deleted), and Sankei News covered the protest. It was also listed on the Yahoo News. Mainichi, which is seen rather as liberal in Japanese media, reported the story just in brief, whereas Yomiuri and Sankei, which are often seen as conservative in Japan, covered it in more detail with Aida's artistic career. The Yahoo news was distributed from a legal website called Bengoshi.com, which pointed out that the art pieces are not considered as child pornography from a legal point of view. An alternative online news site such as J Cast News reported it in more detail with Aida's interview and what the Internet users said about it. Japanese news media for foreigners such as Metropolis and The Japan Times had long art reviews in English with several photos of Aida's artworks. Their articles explored why he made them and what their themes were. The international news press such as Bloomberg Businessweek covered the news, which was then quoted by a blogger of The Huffington Post and reported in its Art and Culture section. These are the articles that can be collected on the Internet at this moment.

Within the limited numbers of the news reports mentioned above, it is fair to say that Japanese media (excluding the ones that reported in English) seem to have reported the story briefly as news, whereas the foreign media (including Japanese ones that reported in English) seem to have reported it as a part of an art review, not merely as news. They are more likely to appreciate Aida's works as art and suggest inspiring comments to the readers. For example, they interpret his works and what they mean to Japanese society like "[His works] depict taboo subjects and also shed light on people's sense of shame" (Daily Yomiuri), "Aida manages to give his paintings a façade of ugliness, inanity and frivolity, while at the same time imbuing them with wit, beauty, irony and pathos" (The Japan Times), and "Pornography is just one of the many devices he employs to provoke the viewer to reexamine everyday aspects of Japanese culture and see what lurks beneath the calm surface" (Businessweek). The blogger of The Huffinton Post even asks the readers to "[s]ee a slide show of the work below, and let us know your thoughts in the comments" (The Huffinton Post). English reporting media is more likely to examine an art event more in depth and offer a controversial point of view for the readers to think about it. In an article of The Japan Times, the writer even analyzes Japanese culture and society through this exhibition ("the painting has [...] something to do with Japan's obsession with cuteness – the so-called culture of kawaii") (The Japan Times).

There are various reasons why the Japanese reporting media just covered the event as news. One of them comes from Japan's poor art-reviewing culture in news media. Usually Japanese mainstream newspapers do not include cultural and art reviews in their weekend editions unlike British and American standard newspapers. Since the Japanese media do not cover an art event in their culture and art sections in depth, an art event is often briefly reported as news. A controversial issue is not likely to be debated on news media outlets, either. Most of all, the main reason that made the issue difficult to debate in news media outlets is the ambiguous definition of the term child pornography in Japan. Under Japan's laws, production, distribution, dissemination, and possession for sale of child pornography depicting children under 18 years of age is a criminal offence since 1999 just like the same laws in other Western countries (except that possession is still legal in Japan). What makes the Japan's child porn laws very different from the other countries', especially those of the U.S., is the ambiguous definition of the term. It is simply written as "arouses or stimulates the viewer's sexual desire." This ambiguity allowed the protest group to call Aida's works "child porn" (PAPS) and made the Japanese media reluctant to go into deeper argument on the issue. The other point that might have made the argument difficult is the fact that vast child pornographic images in Japanese manga and anime are not real and are difficult to certify as child porn. Since the purpose of Japanese child porn laws is to protect junior victims, it is difficult to apply them directly to the anime and manga characters that do not exist in the real world. Even though 86.5% of respondents of a poll are for the regulation of art depicting child porn, the government cannot do so because of the facts mentioned above and also the fear that the laws may infringe the freedom of speech, press, and all other forms of expression. All these arguments on child porn may make Japanese news media hesitate to put in-depth art reviews of the exhibition on their websites.

On the other hand, the English reporting media had a deeper analysis of the exhibition because they have a clearer distinction between porn and art than Japanese media and also regularly publish art their reviews on their pages. In terms of child pornography in the U.S., child pornography is defined under 18 U.S.C. §1466A and §2252A. The provisions are a little more in detail than those of Japan, but the most contrasting feature is that they have a line saying that an image that "lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value" (§1466A) is defined as child pornography. In other words, some artistic pieces are seen as an art piece even though there are some visual elements of sexual abuse of children in it. This is perfectly reasonable and understandable since the provisions may violate the freedom of speech without these exceptions. Hollywood movies such as Traffic and American Beauty could be categorized as child porn and banned if there were no such a clause. The same thing can be said to visual child porn. Actually, the U.S. Government introduced the Child Pornography Prevention Act of 1996, but the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the law in 2002 for the same reason for the protection of art values. The Government again issued the improved PROTECT Act of 2003 instead, but it still cannot ban all the images that they initially intended to. American media, including Businessweek and The Huffington Post, at least have such a legal background to appreciate and discuss the controversial pieces as art, whereas Japanese media may have hesitated to do so because they have a vague legal boundary between art and child porn although its society is full of such images.

However, the main issue that both the protest group and the museum focused on was not whether the art pieces are child pornography or not, but whether they could be displayed in a public place such as a museum or not. In the letter of protest, what the group called for is the removal of related works from the exhibition. Aida was well aware of the problem, too and said, "There are some among my works that can't be openly exhibited in public art museums" in his interview posted on the museum website long before he received the letter from the group. He even said, "I had always thought of some of the works to be displayed in the R18 room (like the "Dog" series) as almost certainly too much for an art museum to show openly" and "I wouldn't think of insisting against everyone's better judgment that my more confronting works be hung in such a public arena." He said this especially because young children may be in the audience of the exhibition. These statements show that he shared the same concerns as the protest group from the beginning and finally decided to display some of his works in the restricted area. The focus of the argument is then more on how artistic values and community standards go together, which is not particularly discussed in any media that was mentioned earlier.

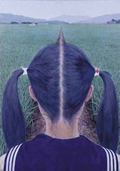

As shown above, English reporting media was more likely to report the art event in a review form to give the readers clues to judge whether it is worth visiting or not, whereas Japanese media rarely offered critical points of views on the event for the readers and just covered it merely as news. This is because Japanese media intends to avoid controversial issues and does not have enough art appreciating practices in its media outlet on a daily basis as a whole. On the other hand, the Japanese media did not really focus on the issue that the protest group and the museum focused on. As The Japan Times' article cited above suggested, it is true that a sense of kawaii, which is often translated as cuteness in English, plays a huge role in people's preference in Japanese society today. There could have been a critical analysis on Japanese society using this term as a key word through the review of the exhibition.